Abp. Charles Chaput is the Archbishop Emeritus of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. He is a professed member of the Capuchin Franciscans, and has previously served as Archbishop of Denver and Bishop of Rapid City

Abp. Charles Chaput is the Archbishop Emeritus of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. He is a professed member of the Capuchin Franciscans, and has previously served as Archbishop of Denver and Bishop of Rapid City

← Return to EssaysStay Connected!

My focus tonight is baptism, but I want to approach it in a roundabout way. So I hope you’ll bear with me for a few moments. I’ll get there; I promise.

I’ve always been a movie fan. When I was very young I wanted to be a stunt man, or a director, or both. Obviously that didn’t work out. But I’ve watched hundreds of films over my lifetime, and some have left a deep mark on my memory. I saw the 1972 film Cabaret many years ago, and I’ve never forgotten it. Cabaret was inspired by Christopher Isherwood’s 1945 book, Berlin Stories. It’s a portrait of the cultural and sexual anarchy in Weimar Germany, just before the Nazi takeover. It’s not a family film. And it’s definitely not a “Christian” film. But the director, Bob Fosse, was a man of real genius. So watching it – especially through the lens of historical hindsight – is a compelling experience.

It’s also instructive. And here’s why.

Sometime in the next week, I want you to search the words “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” on YouTube. Open the videoclip from the Cabaret movie. Then watch the film’s biergarten scene, and listen to that song — “Tomorrow Belongs to Me.” And do it several times. The lyrics are important. But it’s the editing of the faces, and the orchestration of the song, that are truly brilliant. The tune begins as a gentle ode to nature, sung by a young man’s angelic voice. But the young man belongs to the Hitler Youth. And the song, joined by a few of the customers, and then more and more of the customers, builds into a chorus of mass fanaticism. The scene is a perfect portrait of man’s oldest and most persistent sin: idolatry. In Germany’s case, it was worship of the Fatherland; the delusion of a master race. But if the human story teaches us anything, it’s that idolatry has an infinite wardrobe of disguises, and an endless number of victims.

The Third Reich euthanized some 300,000 mentally and physically disabled persons. Then it killed another 6 million Jews, Gypsies, social outcasts, and political prisoners in the name of Aryan racial purity. The political heirs of Karl Marx — Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and others — murdered 25 million people in the Soviet bloc; 40 million in China; 2 million in a nation of just 7 million in Cambodia; and millions more elsewhere – all to create a new world and restart history from “Year Zero,” cleansed of any memory of the past, on the model of man as his own master; humanity as the real and only god.

The body count from the last hundred years is both well documented and painful to revisit. We’ve learned — or at least we think we’ve learned — an important lesson. And the lesson is this: Any political party or ideology that claims to create a new kind of man, a self-sustaining, self-redemptive humanity, is a fraud. It’s just the latest installment in a very old gnostic fairy tale. Gnosticism grew up alongside Christianity, sometimes intertwining with it; and the modern gnostic zealot – whether he calls himself a fascist, a Nazi, a Marxist, or even a certain brand of progressive – is never really irreligious. And he’s certainly not an “unbeliever,” even when he says he is. He’s a particular kind of believer; a man convinced he has the secret knowledge, the gnosis, that unlocks the power to fix a broken world. And he clings to that sacred knowledge just as religiously as any 14th century monk clung to his Bible.

The difference, of course, is that the God of the monk was true. The god of the gnostic isn’t. Each new version of the gnostic zealot dresses up his little godling in new language with new tools of coercion. But underneath, it’s always the same idolatrous lie. Man is not a god, and there’s no secret knowledge that can make him so. He didn’t create, and he doesn’t command, reality. And his lies always exact a premium in suffering, especially among the weak. The idols that man makes with his own hands – whether they’re golden calves or political theories – always betray their worshipers. They’re vampires that live off humanity’s hopes and fears.

But if that’s so, why would anyone believe in a regime of lies? Why would people swallow toxic nonsense like Marxist economics or Nazi racism? The answer is that most people, being reasonably intelligent, don’t believe in a system based on deceit. But that doesn’t stop them from complying with it. They’re weak, or intimidated, or despairing, or just too lazy to speak the truth until it’s too late to make a difference. Many people – probably most people – will try to live as normally as they can, for as long as they can, no matter what the nature of their political and cultural environment. Most Russians weren’t Bolsheviks. Most Germans weren’t Nazis. But they went along, to get along. They did what they needed to do in order to survive, while the world went dark around them.

The trouble with “going along to get along” is that it tends to poison both the brain and the soul. A life of avoidance and non-resistance in a regime of big lies and real wickedness sooner or later becomes just a pile of smaller lies under a thin dusting of alibis. And here’s another fact. Most people – a great many people – simply yearn to give themselves away. That may sound strange, but we humans are social creatures. Loneliness is a curse. No one wants to be an outsider. We yearn to belong to something bigger and more meaningful than ourselves. If that “something” isn’t God, then it will be something else; even something that’s a bitter enemy of God . . . which accounts for why otherwise decent men and women lose themselves in homicidal illusions and mass fanaticisms.

Every unconverted human heart has a secret crevice in its flesh. And hidden in that crevice is the laboratory where we perfect the flavor of our resentments; resentments that we then project outward onto others whom we demonize — kulaks, Jews, ethnic and racial minorities; anybody will do; the nature of the victims really doesn’t matter. An unredeemed appetite for enemies — their humiliation and their destruction – is a primordial human addiction. Augustine called it our libido dominandi; the will to power, our hunger to dominate. Hatred is poisonous. But it’s also, in a terrible and fatal way, exhilarating. The reason is simple. Hatred isn’t the opposite of love; it’s love’s deformed mirror-image, which is why it has such power.

The good news is that our country was created to be a different and better place. It was designed to be – and always has been — an experiment in ordered liberty, a mix of biblical realism and Enlightenment hopes. It’s never been perfect. Nothing human ever is. But in so many ways, it actually works. And it’s worth fighting for. We have the kind of laws and freedoms, the public institutions and civil consciousness, which ensure that things like the murderous obsessions that ruined the last century can never happen here.

Or at least, that’s what we think. The not-so-good news is that we can lose everything we have. As Solzhenitsyn once said, “prosperity breeds idiots.” The proof is in our current political terrain, and especially in the leaders who now shape it. Nothing makes us immune to stupidity, or idolatry, or fracturing as a culture. The United States is a country with a reservoir of great goodness and great people. But no nation is permanent, and that includes our own.

Exactly 14 years ago, in the months leading up to the 2008 election, I published a book titled Render Unto Caesar. I wrote it for a young friend, a husband and father, who asked me to do it. Chris was a Catholic prolife Democrat who had previously run for state office, and almost won, in a Republican district. He wanted advice. He wanted to know the proper role of religious faith in public life. And he specifically asked for counsel about how a Catholic political leader should integrate his Christian beliefs with his political service.

I browsed through that old book as I was getting ready for today. It turns out I was a lot smarter back then. What I said in those pages is pretty simple. The Christian faith is about much more than politics. And politics, as we’ve already seen, can very easily become an obsession; a form of idolatry. But to get to the City of God, we need to pass through the City of Man. And in the City of Man, politics is a necessary part of life. Politics involves getting and using power — for good or for evil. Thus, power has an unavoidably moral dimension. Which means that Christians do have a duty to be involved in public discourse and political life in order to help build a better society.

Two of the quotations I used in that book from so long ago have stayed with me over the years. The first is from the writer Charles Peguy: “Freedom is a system based on courage.” The second is from the philosopher Henri Bergson: “The motive power of democracy is love.” I still believe in those words. It’s true that real freedom can be degraded by license, and democracy, absent a commitment to love, can be corrupted by envy and bitterness. But there’s not much in my book I would change.

What’s changed is the nation I wrote it in. We’re not the same country, and increasingly not the same people, we were as recently as 2008. Fourteen years ago there was no Obergefell decision, no national mandate for gay marriage, no 1619 Project, no – or at least much less – Big Tech political censorship, no library drag shows for kids, and no smearing of public school parents as possible domestic terrorists. Critical race theory, woke-ism, and transgender rights were, all of them, obscure obsessions of the elite.

These changes are not accidents of history. They’re not just ill-advised and unhealthy. They’re intentional. They’re vindictive. In some ways, they’re truly wicked. They quite consciously target the biblical moral universe that has informed our country since its birth. And this is why Eric Voegelin, the great political philosopher who fled Nazi Germany for the United States, had such a deep distrust for modern progressive politics. He saw, in self-described “progressive” thought, not just an exercise in moral preening, but the same destructive instincts — more muted, but just as real — that he found in fascism and Marxist thought.

So what’s the result?

A friend of mine likes to say that our current political reality boils down to “narcolepsy for the masses;” narcolepsy as policy; narcolepsy by design; in other words, a populace permanently half asleep and thus easily molded and led. That may sound odd. But it’s really just a variant on what the media scholar Neil Postman wrote in his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, and what the social historian Christopher Lasch said in his book, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. Neither Postman nor Lasch, by the way, came from the political right. Both men were very rational voices on the democratic left. And both men saw that so much of our current culture is actually based on weakening rather than strengthening the individual; creating dependence rather than real autonomy.

Modern American life is dominated by science and technology, to the exclusion of what we once called “the humanities,” and to the erosion of people’s interior life. The social sciences, in particular, have a very ambiguous view of what a human being actually is. Society, through the lens of these tools, becomes less a living community of free and independent persons, and more a tangle of managerial problems that need to be solved; a complex machine that needs constant fine-tuning and guidance by experts. And that has consequences.

Real human persons are messy and fractious. They’re stubborn. They have unhelpful ideas. They don’t really understand what’s best for them. So they need the kind of bread and circuses that allows the serious business of governance to proceed. In the end, we get a stupefied populace of narcoleptics addicted to trash media, materialist junk, fast food, and the internet. In other words, people unable to think, people who need to be ruled — and surveilled, for everyone’s safety — by really smart other people . . . which is the exact opposite of what our public life was designed by the Founders to require. It’s also uncomfortably close to the world C.S. Lewis worried about in The Abolition of Man. That’s where we are now.

So what do we do about it?

Some of you might recall that this talk is supposed to be about baptism. So to baptism I’ll now turn. And the best place to start, oddly enough, is a couple of Czech dissidents.

The title I chose for my comments tonight is “On the Power of the Powerless.” And I borrowed it from one of the great essays of the last century. Václav Havel, the playwright and political dissident, wrote “The Power of the Powerless” in 1978 at the height of communist repression in his native Czechoslovakia. The content is brilliant, but Havel’s main point is very simple. Even in a world of persecution and state control, the individual is never really powerless. He or she always has the power to say no; to refuse to believe lies; and to search out other people who share a love for truth and are willing to suffer for it.

Havel was never religious. But his friend and fellow dissident, Václav Benda, was. And Benda’s the man, Václav Benda, whose example I want us to remember as we leave here tonight.

A husband and father of six, Benda — when he was pressed in the 1970s to join the Communist Party for professional reasons — declined to do so. It killed his career. He was hounded out of academia. He was forced from one menial job after another. He was harassed for his peaceful resistance activities, which were technically legal under Czechoslovak law. He was a prominent leader in the Charter 77 human rights movement and a cofounder of VONS, the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted. He was arrested and jailed for four years. But none of it deterred him. He and his family had a profound Catholic faith, and they lived it intensely. At Easter in 1985, in the midst of all his political problems and government hassling, Benda wrote an extraordinary defense of Catholic teaching on divorce, contraception, and abortion – this, despite knowing that part of the Czech Church was collaborating with the regime, and some of her leaders were both corrupt and cowards.

Benda’s collected essays, published in English as The Long Night of the Watchman, are deeply moving, and they’re animated throughout by the light of Christian courage. And through it all, he never lost his gratitude for the beauty of his family, the gift of his faith, or a sense of humor about his own sufferings. He wrote that “I consider it extremely unreasonable, once you’ve shown some eccentric willingness to throw yourself to the lions, to complain that their teeth are not very clean.”

So here’s the point of our time together tonight. All of this man’s energy, creativity, and courage flowed out of one source: his identity and fidelity as a believing Catholic layman – the vocation which began at his baptism and shaped his whole life. As Péguy said, Freedom is a system based on courage, which is why even in his prison cell, Václav Benda was a free man; free in a way his persecutors could never be.

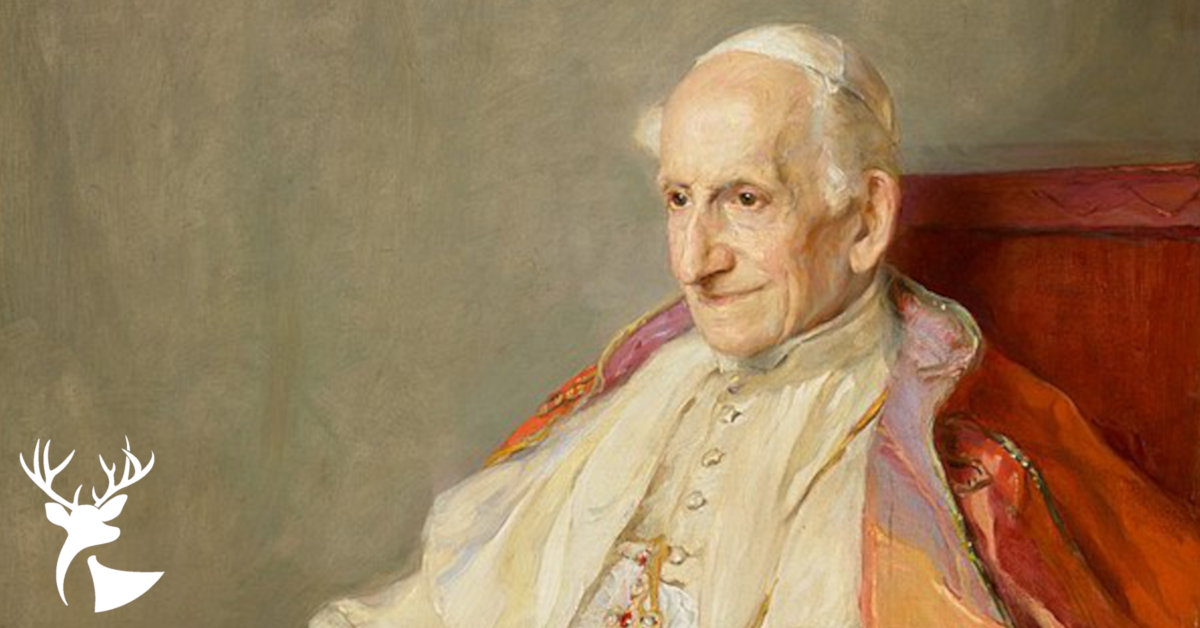

Most of us in this room know that baptism is the foundation of every other sacrament and every Christian vocation. The Eucharist is the source and summit of Catholic life. But it stands on the cornerstone of baptism. And we know that baptism does three things: It washes away Original Sin; it incorporates us into the living community of God’s people, the Church; and it gives us a share in the life of the Holy Trinity. In other words, it makes us a new creation, with the possibility to think and act in a godly way, through the teaching of Jesus Christ. Baptism gives us the energy of Christ’s resurrection for our lives here and now, and not just in eternity. And all of this is not of our own doing; it’s a free gift and matter of grace. This is why true Christians, believing Christians, are always a threat to the powers of this world.

For us American Catholics, these truths about baptism, and all the articles of our faith, have been easy to learn, easy to affirm, and too often easy to forget, for the last six decades. The Church in our country has enjoyed a fairly free and comfortable life for a long time. And a great deal of good has been done. It’s still being done by good people in every American diocese and parish. We should be grateful and proud for all that God has made possible, and our place in it. But if the hatred unleashed by the recent Dobbs decision teaches us anything, it’s that our comfortable times – the go along and get along times – are over. We need to think and act accordingly. We need to recover the spine and the missionary nature of our baptism.

There’s a curious irony in our culture’s use of words like “enlightenment” and “woke-ism.” Both words suggest a waking up from the past to a future of reason and light when, in practice, they often create just the opposite – a surplus of conflict and darkness, here and now. No technology, no “ism,” and no special knowledge can ever replace man’s need for God. Idolatry, whatever form or name it takes, always betrays us. Only God is God, and Jesus Christ is his Son and our Redeemer. We need to remember Romans 8:31. We need to burn that Scripture verse into our brains and carry it in our hearts: “If God is for us, who can be against us?” A life lived in fear, a life spent seeking some kind of concordat with ideas and behaviors that are truly wicked and celebrated now in so much of our culture, is never the path for a Christian. It’s always a destructive lie.

If Václav Benda, and others like him, could speak and work for the truth, with far fewer resources and in circumstances infinitely harder than our own . . . then surely we can do at least as much, no matter how difficult our own world becomes. So this isn’t a bad time to be a Christian. It’s exactly the best time, because it’s our time to prove that we really do believe what we claim to believe, by preaching it with the witness of our lives.

Jesus said, “I am the light of the world.” He’s the only true light of the world. So we are not powerless; we’re neverpowerless; because we’ve been baptized into the cross of the God who loves us.

And if God is with us, who can be against us?

This talk was originally written for the Bl. Alcuin of York Lecture, Oct. 7, 2022

More Reading

Abp. Charles Chaput is the Archbishop Emeritus of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. He is a professed member of the Capuchin Franciscans, and has previously served as Archbishop of Denver and Bishop of Rapid City

Thank you so much for posting this lecture! It was most excellent! I am grateful to have it in writing, for hearing it was incredible, but I needed/wanted to slowly absorb it again (and probably again). 🙂

And for that matter, thank you for posting all of the homilies, lectures, and writings on your website. The website is a treasure of reading!

Thanks for the kind words, Lisa. I am glad the you enjoyed the lecture. I know I did as well! God bless.

This was so powerful and hit home with me on almost every paragraph when I reread it after hearing it spoken by Bishop Konderla. I too, can no longer “go along so as to get along”, especially with family and friends. The truth spoken with the love of Jesus Christ always prevails.

Thanks, Judene! I certainly agree. I’m glad you all were able to make it to Tulsa for the lecture. God bless.