Dr. Richard Meloche serves as the president of the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.

Dr. Richard Meloche serves as the president of the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.

← Return to EssaysStay Connected!

“I, your Flaccus [Alcuin], am doing as you have urged and wished. To some who are beneath the roof of St. Martin I am striving to dispense the honey of Holy Scripture; others I am eager to intoxicate with the old wine of ancient learning; others again I am beginning to feed with the apples of grammatical refinement; and there are some whom I long to adorn with the knowledge of astronomy, as a stately house is adorned with a painted roof. I am made all things to all men that I may instruct many to the profit of God's Holy Church and to the luster of your imperial reign. So shall the grace of Almighty God toward me be not in vain and the largess of your bounty be of no avail.”

—Bl. Alcuin of York

Epistle 48 (to Charlemagne)

Interesting conversations almost always begin with a bold, polemic statement. So, allow me to begin this series by stating an obvious but seldom admitted observation: our modern age is motivated by an irrational faith in the ‘new’. If it is new it is presumed as somehow being better by mere dint of fact of its relative novelty. As proof of my claim, take for example the latest craze for the newest technology—the 2.0 is unreflectively deemed superior by virtue of its release date.In saner times, the value of an object was weighed by its age and endurance. The reliable ‘test of time’ was held to be the best judge of the particular merit and value of a thing. If a thing still proved to be relevant after generational use – then heck, it must be good.

This was most surely the thinking of Bl. Alcuin of York (b. circa 735 a.d.). When Alcuin was appointed the minister of education for the newly established Holy Roman Empire, he was charged by Emperor Charlemagne to intellectually invigorate an entire nation that had fallen into a mental stupor. Centuries before, when the barbarian hordes had invaded Rome, they did their best to destroy all that was good, true and beautiful, including the many and various monasteries that populated the land. These monasteries, with their vast libraries and learned and holy men, were the centers of learning (colleges/universities did not exist), and when these were blotted-out the acumen of the people, understandably, atrophied.

Importantly, in order to reverse course, Alcuin did not implement the latest educational fad but, instead, turned to the past in order to positively affect the future. He knew that certain pedagogies had proven most effective in forming good habits of the mind and he also knew the specific body of knowledge that the great thinkers of old had arduously studied and learned. With this knowledge in hand he implemented his reforms. He ordered a very simple ‘program’ of manuscriptual transcription (aka the copying of old books). He insisted that every ancient text that had survived the centuries of neglect be painstakingly replicated—letter by letter and word by word. By doing so he was advancing both a proven educational pedagogy, viz. copy work and, simultaneously introducing the copyist to the proven wisdom of the ancients.

As a result of Alcuin’s strategic turning to the past an educational, and in turn a cultural, renaissance was begun. His efforts resulted in what historians call the Carolingian Renaissance: an intense and long period of unparalleled human flourishing. All of this to say that there is not only precedence in our Catholic tradition in looking to the past to positively affect the future, but there is proven wisdom and utility in doing so. The past has much to teach us if we but simply have the humility to turn to our forebears and seek in earnest their aged—and time-tested—counsel.

Hence, this series will be devoted to explicitly turning to the wisdom of the many and varied voices of our Catholic heritage. We will be looking not only to the intellectual giants, such as Augustine, Aquinas, Newman, and Thérèse, but to more obscure, and often forgotten members of our Catholic family, like Alcuin of York and John Damascene. More specifically, this series will be plumbing the wisdom of our tradition on a particular theme, namely the mystery of the human person.

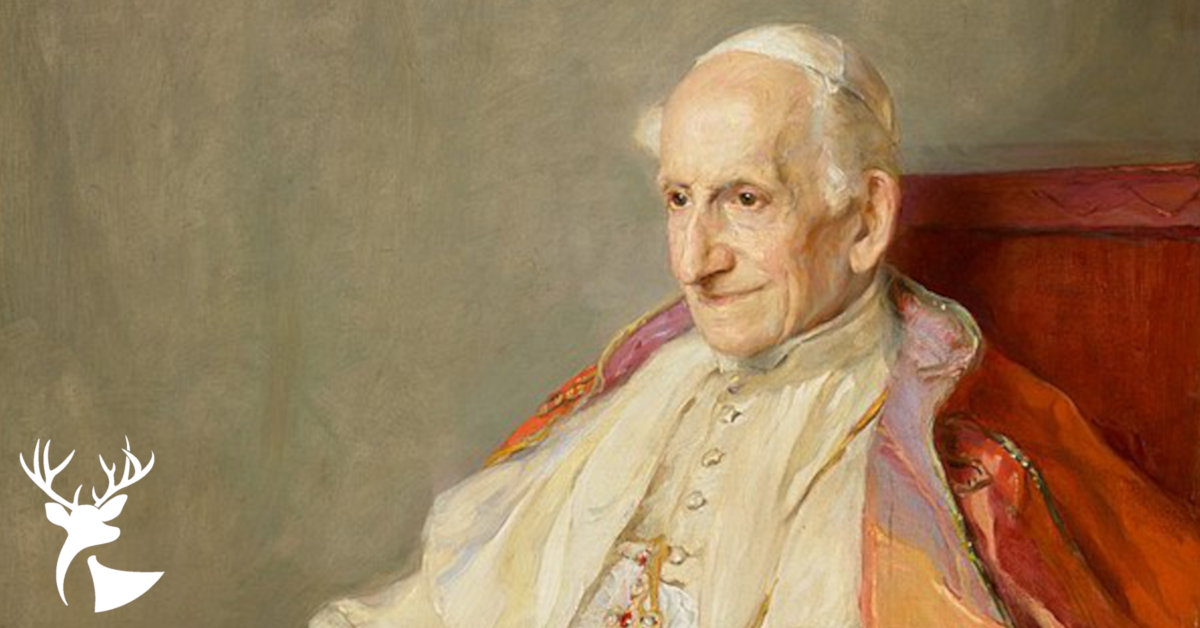

We have chosen to explore this theme of the human person on account of the growing confusion concerning the nature of man and the subsequent increased threat to human life and dignity. Twenty-five years ago, Pope St. John Paul II worried that various new scientific and technological advancements would lead to sinister legislation and profound popular norms that would undermine the very truth and goodness of persons. This is more true now than in 1995 when JP II penned Evangelium Vitae. Take for example that almost a quarter of all Americans (22%) believe that man is no more than a sack of randomly organized cells (cf. 2019 Gallup survey on Creationism), and just under half of all Americans (40%) believe that there is a range of possible gender identities that are in no way implicitly tied to one’s biological sex (cf. 2019 PRRI survey on Transgenderism).

These mistaken and tragic views on the nature of the human person, no matter how well intentioned, need the illuminating and purifying light of the Gospel and sacred Tradition. It is ultimately the mystery of the Incarnation—the God-Man, Jesus Christ—that fully reveals man to himself (cf. Gadium et Spes, 22) And what does Christ reveal about human nature? The Incarnation (Lat.: in + caro, literally ‘to be made flesh’) reveals, first and foremost, the utterly unique and extraordinary place that man occupies in the vastness and beauty of the created cosmos. Out of an unfathomable love God chose to unite Himself to man.

Furthermore, as the Catechism informs us, man is also quite special on account of four qualities that he singularly possesses, namely: (1) that he is made in the imago Dei – the image of God; (2) that he is – what the philosophers call – hylemorphic, that is, in his own nature he unites the spiritual (angelic) and the material (bestial) worlds; (3) that he is created “male and female”; and lastly (4) that God established him in “friendship” with Himself (CCC, n. 355). These are profound truths that when deeply understood and truly appropriated effect not only how we see ourselves but how we relate to others and to God. Thus the necessity of turning to our tradition to help us plumb this very essential and important mystery: the mystery of the human person.

Throughout the year we will be enlisting a bevy of learned contributors to help us enter more deeply into the mystery of man. They will be turning back to our shared intellectual patrimony in order to shed light on particular thinkers who have written profoundly and/or eloquently on the nature of the human person. The contributors will assist us in understanding what exactly the ancient authors are saying and help us ponder anew how the truths conveyed thereby can positively influence our own understanding and interactions with the modern world. In addition to the merry faculty of the Alcuin institute (Dr. Christine Myers, Dcn. Harrison Garlick, Mr. Joey Spencer, Eli Stone, and Mason Beecroft) we are pleased to announce that Dr. Donald Prudlo, the new Warren Professor of Catholic Studies from TU, will also be contributing to the series.

In the opening quote of this essay Bl. Alcuin analogously refers education to feasting. The learning of grammar, writes Alcuin, is like the consumption of apples: not particularly enjoyable, but necessarily good for you. The study of Holy Writ, alternatively, is likened to the eating of honey: palatable, sweet and utterly satisfying. “Ancient learning,” however, according to Alcuin is akin to drinking “old wine”: deep, flavorful, and intoxicating. Like the consumption of old wine, the learning of ancient truths, transmits a depth and a richness that is unrivaled by the new. In this series we thus invite you to turn away from the new (at least for a while) and to drink deeply from the fermented treasury of our ancient past. Enjoy!

More Reading

Dr. Richard Meloche serves as the president of the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.