Odysseus, Aslan, and Untamed Catholicism

We find our hero Odysseus on his journey home from the Trojan war. Ten years he fought on the plains before Troy; and now ten years more he will journey…

On Christ’s Invitation to Chaos

Water is chaos. Water is death, disorder, ugliness, and confusion. As Holy Scripture teaches us, after God had made the heavens and the earth, the earth was, in its primal…

On Faith & Fortitude: The Shield of Sir Gawain

On New Year’s Eve, King Arthur was with his knights and other guests at the round table. As was his custom, King Arthur would not begin to eat until he…

On the Poem the Pearl & Seeking the Higher Good

We come upon a man who has lost something. A spotless pearl has slipped through his fingers and is now lost in the earth. He grieves and cries. His heart…

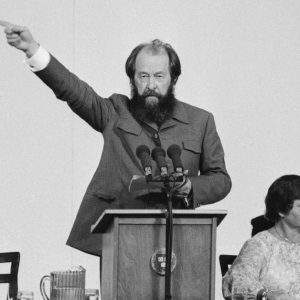

Solzhenitsyn and True Freedom

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn stood before 20,000 people at the 1978 Harvard graduation ceremony. Aleksandr, a Russian, had spent ten years of hard labor in the Soviet gulags on trumped up charges…