Dr. Aaron Henderson is a Faculty Tutor for the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.

Dr. Aaron Henderson is a Faculty Tutor for the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.

← Return to EssaysStay Connected!

We are by nature social or political animals. We find our full flourishing as human beings not in isolation but in communion with other persons. And so Christ’s injunction not to be of the world (Jn. 17) does not necessitate being some place other than the world in which we live and act. In short, Jesus’s words relate not to our origins but to our affections or desires. Being “not of this world” means seeking first God’s kingdom and His justice, confident that if we do, He will give us our temporal necessities also (Mt. 6:33). It is with this fundamental mentality that Christians, animated by the word of Christ, engage in temporal political affairs.

The problems of the modern age in general, and those of our contemporary socio-political context more particularly, call for well-wrought solutions. But where do we seek these solutions? Not, surely, in the pseudo-logic of momentary fads or of reactionary movements. Instead, we look to the wisdom of the past, to the paths trod by our ancestors. We do this not because our forebearers were perfect, but because human beings of every age seek the truth in part by appealing to a great tradition, which G.K. Chesterton strikingly called “the democracy of the dead.” More than this, as Catholics we appeal to the theological tradition as well as to the philosophical, to faith alongside reason. Why? Because the Church has a message not only about the natural moral law and about how we ought to act together for the sake of the common good of the social order naturally understood, although she does; the Church also has a supernatural message that ought to take root in the hearts of every human being and in every human community. The latter message purifies, perfects, and elevates the former message.

This explains, at least in part, our rationale for hosting the upcoming Faith & Culture Conference, to be held May 12–13 at the Doubletree Hotel in downtown Tulsa. We intend it to be a conversation between great minds, both local and national, about perennial principles and questions. The goal is not merely heady or academic. These conversations have real potential to change the political landscape for the better. An informed, conscientious populace can only conduce to a wiser and more just nation. I would like to discuss a subject that will inevitably color and animate many of the discussions at the May conference: liberalism. The term “liberal” can mean different things in different contexts. In an American context, liberal can designate someone left leaning politically, and thus it may prove a scornful term for those who are “conservative.” On the other hand, liberal is used as a term of praise by more traditionally minded folk when describing a particular notion and method of education. I am not using the term, therefore, to speak about liberal Democrats or about liberal arts education. I am using liberal here in a more general way to denote something that has been consistently rejected and condemned by the Church, nonetheless something that, to our detriment, permeates every aspect of our social or political life.

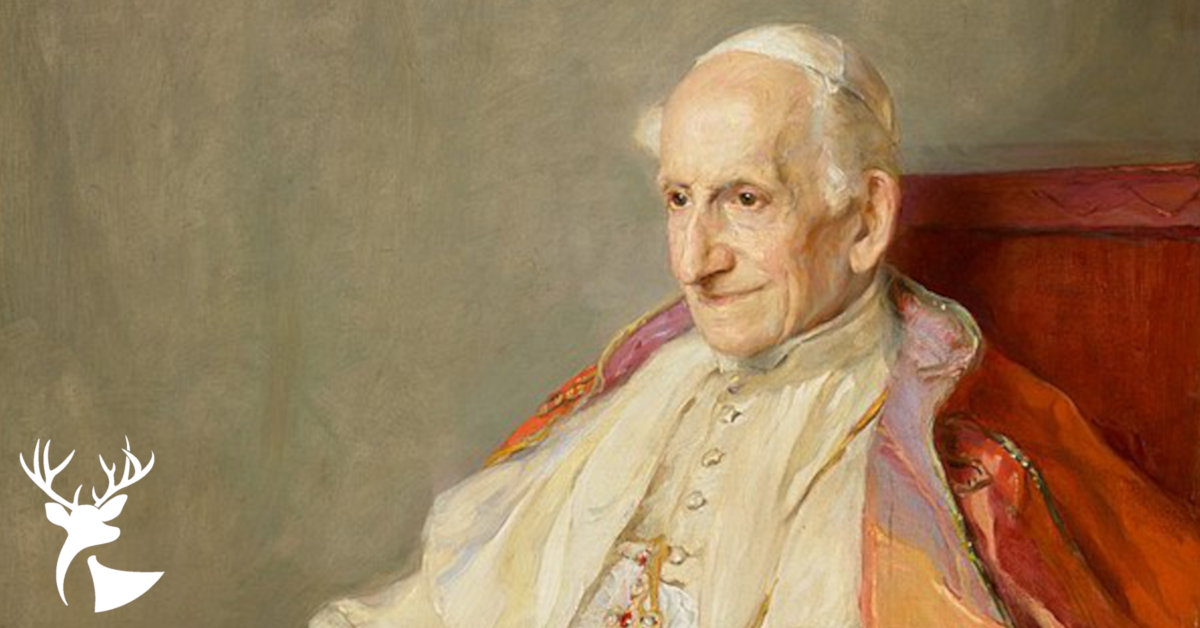

What is liberalism? Simply put, liberalism is the undue exaltation of freedom (libertas) above all other social or political goods. Liberalism makes human freedom the chief goal or end of political life. At root, it is based on a tendency, quintessentially modern, to make “will” (as opposed to intellect) the highest principle in human life. Human reason is a measured measure, by which I mean that it is the measure or rule of our actions, yes, but one that is measured or ruled by reality. It is only when we have conformed our minds to reality that we can reach out in love to the good. Or so it is when we properly order intellect and will. Liberalism, which exalts unfettered will and freedom, exists in the theological realm as well, and these two manifestations of liberalism are not unconnected, as Pope Leo XIII argues in his encyclical Libertas:

[F]ollowers of liberalism deny the existence of any divine authority to which obedience is due, and proclaim that every man is the law to himself; from which arises that ethical system which they style independent morality, and which, under the guise of liberty, exonerates man from any obedience to the commands of God, and substitutes a boundless license. The end of all this it is not difficult to foresee, especially when society is in question. For, when once man is firmly persuaded that he is subject to no one, it follows that the efficient cause of the unity of civil society is not to be sought in any principle external to man, or superior to him, but simply in the free will of individuals; that the authority in the State comes from the people only; and that, just as every man’s individual reason is his only rule of life, so the collective reason of the community should be the supreme guide in the management of all public affairs.

If you can easily see our own societal moment even in these words from 1888, it is because liberalism, just as Leo XIII describes, is the air we breathe, the water in which we swim, the inescapable presupposition to every political action we take. Bound up with liberalism is an understanding of human rights based not on the goods and ends of human nature, especially those goods we call “common” because they are communicable to many without diminution, but based on a negative precept never to violate the desires of another citizen. Notice that the legitimacy or illegitimacy, the uprightness or perversity, of these desires is immaterial. In a world in which will reigns supreme, it matters not what I have chosen or why; it matters simply that I, a free subject, have chosen it.

First, individual human freedom should not be elevated above all other goods, since the private good is always ordered to the common good, and since law itself as a principle of order in society is an ordinate of reason precisely for the common good. Second, however, the vision of freedom I just described is not the Catholic vision, nor a traditional vision of any kind. For freedom is always founded and grounded in the truth, in an understanding of the wise and good order that God has made and willed for us to inhabit. Human freedom blooms in the soil of truth and responsibility toward our neighbor, to say nothing of our responsibility to Almighty God. It does not grow or bloom in the soil of indifference and self-centeredness. Sometimes these competing visions of freedom are called “freedom for excellence” and “freedom of indifference” respectively. The former gives rise, when appropriated by the members of a nation, to more peace, more justice, more social solidarity. The latter gives rise, as we see daily in our own nation and abroad, to more violence, more malice, more social discord.

Because all interpersonal interactions in the modern world are suspected of being fronts for manipulation and the will to power, the social contract is thought to protect us and to ensure that our “rights” (whether rights in truth or mere licenses to do whatever we want) remain unviolated. However, this need not be the solution, in part because the premise on which it is based is false. True enough, human relationships in this fallen world are subject to abuse and manipulation. Even still, a reorienting of our fundamental narrative, one in which will is paramount, would do much to alleviate the ills of the modern age. Human beings are not political because the social contract is the only way to ensure that we do not routinely plunder and pillage one another. We are political because we have powers of intellect and will that impel and compel us to enter into relationships of knowledge and love with other persons. We find real fulfillment in these communions, even if we are ultimately called for supernatural communion with the Triune God and with those likewise joined to Him in faith and charity.

If casting off the chains of liberalism seems impossible or even undesirable, it is, again, because liberalism so profoundly characterizes the modern project. Voluntarism, nominalism, subjectivism, relativism—these are so many interdependent poisons that weaken us and our society. Granted that liberalism is but one “topic” among many, it is sure to make an appearance at the Alcuin Institute’s Faith & Culture Conference. If you are interested in learning more about the relationship between Church and state, between Catholic culture and (American) political life, do join us on May 12–13! We would appreciate your help in understanding the principles involved and in crafting practical solutions for living as Catholic citizens in a rapidly changing world.

More Reading

Dr. Aaron Henderson is a Faculty Tutor for the Alcuin Institute for Catholic Culture.